Presently farmers are playing a passive role in the value chain and are dictated in their actions by traders and other intermediaries. Value chain development efforts aim at making the present community production system an active player by positioning farmers within the market system in the process of addressing markets related needs to their advantage.

Of the many agricultural activities to be pursued, one that assumes importance is the development of ginger sub-sectors in the state. As this sub-sector has the characteristics that place it well (naturally endowed land and prevalent micro-climate in the state) and form a substantial share of the state’s agriculture economy wherein most households are involved in its cultivation. Ginger in particular is considered by farmers as their “ATM”, a ready source of money which is many a time left growing in the field and harvested only in times of need.

The need for value chain planning and execution stems from developing a deeper understanding of the market and related requirements, and of the role of players involved in the product’s handling process, as it moves along the supply-chain. Once an understanding has been developed, efforts can be directed at addressing areas that can be influenced to optimize costs associated with every activity to make the product more competitive from a market standpoint. This approach encourages producers to look at market expectations and work backwards to conform to such requirements, thus bringing synchronization to the efforts planned. This is achieved through a series of Multi Stakeholders Platforms (MSPs) at state, district, block, cluster and village level to identify gaps and interventions for the value chain.

In attempting to develop the ginger value chain, a number of challenges have risen which need to be addressed systematically and holistically. Some of the key issues include:

The off season production cycle could be a key unique selling point (USP) that could fetch high returns for farmers. In terms of investments, institutional buyers will be more open if a secure chain of custody is developed for Organic produce. Besides this, collective organization in terms of production and marketing could change economies at the input and market end. There is an existing market for retail spices in the North East region and this can be tapped by pursuing organized efforts that meet the needs of quality as per demand.

In terms of production, there is ample scope to improve the ability of land and farmers to pursue improved inter-cropping and use improved varieties to yield higher returns to farmers. Further, improved storage facilities could free the fields from occupying, un-harvested ginger for other crops that can yield returns.

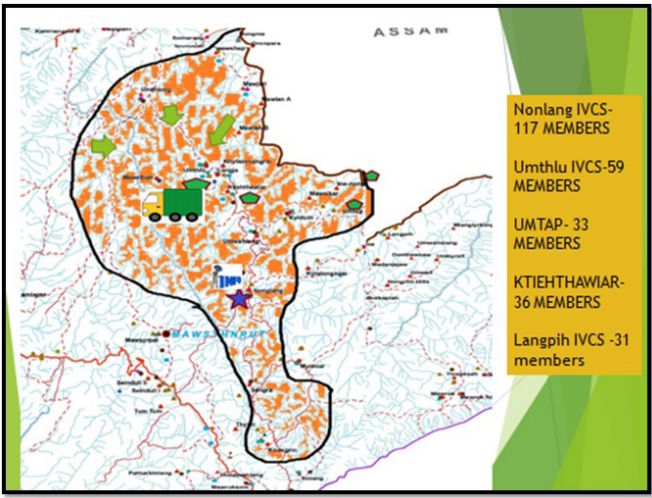

Under the Meghalaya Livelihood and Access to Markets Project (Megha-LAMP), a survey of ginger production was conducted in 60 villages. The results revealed that about 19,80,300 kgs of ginger was produced from 1,819 acres belonging to 3,258 households. Sowing is generally done during March and April. Harvesting of mother Rhizome is generally carried out between July to September. December to February is considered to be the main harvesting month. Other key insights obtained are highlighted below:

| AVERAGE MARKET PRICE VARIANCE 2015-2019 | |||||

| YEAR | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | 2017-2018 | 2018-2019 | 2019-2020 |

| LOWEST PRICE (Rs/Kg) | 800 per Mon/40kg | 1200 Mon/40kg | 1200 Mon/40kg | 3000 Mon/40kg | 3000 Mon/40kg |

| MAXIMUM PRICE (Rs/Kg) | 1500 Mon/40kg | 1500 Mon/40kg | 1500 Mon/40kg | 4000 Mon/40kg | 5000 Mon/40kg |